Engineering soil microbes to fix atmospheric nitrogen and reduce the use of synthetic fertilizers in cereal crops is a hot space in ag biologicals. But to truly deliver on their promise, nitrogen-fixing bugs need to up their game, says Michael Miile, PhD.

The first wave of products (from Corteva and Pivot Bio) have been on the market for three or four years, but there are key technical challenges facing all players in this space if they want to have a transformative impact, says Miille, who became CEO of Bayer/Ginkgo Bioworks-led joint venture Joyn Bio in 2017 and now heads up Ginkgo’s ag bio team.

In 2022, Ginkgo absorbed Joyn Bio after taking over Bayer’s R&D function for biologicals and its West Sacramento, California lab, leaving Bayer to focus on commercializing products emerging from the partnership, which has just been renewed.

To have a major impact on cereal crops, you ideally want microbes that can be applied as seed coatings with a shelf-life of two or even three years (not two months, as some current offerings promise) with higher rates of efficacy across multiple soil types, regions, and crops, Miile told AgFunderNews.

“Nobody’s yet hit a solution that can consistently replace 30% or 40% of synthetic fertilizer. This has always been the target we had, going all the way back to when we were Joyn Bio,” he added.

How nitrogen-fixing microbes work

Legumes such as peas and soybeans have a symbiotic relationship with naturally occurring soil microbes. These colonize the plants’ roots and form nodules that fix atmospheric nitrogen and produce an enzyme (nitrogenase) that converts it into ammonia, which serves as a natural fertilizer.

This offers greater nitrogen-use efficiency than fertilizers that are applied to crops as the microbes deliver nitrogen directly to roots in sync with plant demand, reducing leaching, runoff and volatilization losses. A continuous supply of nitrogen also helps maintain yields when synthetic nitrogen is less available.

Firms in the ag biologicals arena are engineering microbes to perform the same task in cereal crops such as corn and wheat, which do not naturally fix nitrogen, and as a result, use much more synthetic fertilizer, explained Miile.

“Something like two-thirds of the nitrogen usage for a corn plant is in the last third of its growth [cycle]. The growers have this challenge of putting nitrogen into the field at the beginning of the season, but by the time it gets to the last third of the cycle, a lot of it has been depleted, run off [washed away by rainfall or irrigation] or diluted [due to heavy rain, for example], when it’s needed the most.

“Which explains why the levels put out there are so high, so enough stays around for that last third. If we find a microbe that can actually live and transfer nitrogen through the entire growth season, obviously that’s going to hugely impact the amount of synthetic fertilizer growers have to apply at the beginning of the season.”

The technical challenge

The challenge, says Miile, is producing a shelf-stable product that can be applied as a seed coating with a lengthy shelf-life.

“You can apply these things in-furrow or as a foliar treatment, but to have a major impact, both environmentally and cost wise, you really have to have a seed treatment that is stable for a long time.”

The bugs, meanwhile, have to proliferate, colonize plant roots, and stay around long enough to supply nitrogen to the plants throughout the growing cycle, he said. This is one thing in a lab setting, but a different kettle of fish in the real world where native soil microbes can outcompete them surprisingly rapidly.

On top of that, they need to be able to transfer nitrogen efficiently to the plants, and work across different soil types, climates, and crop genotypes, he added.

“That’s why the standard for evaluating all these products is field trials. Sometimes, when you go out to the field with all of the environmental variables, they may not work as well, or work in certain areas and not others. The challenge with biological solutions has always been consistency relative to chemicals. Whereas synthetic fertilizer pretty much works anywhere, whether it’s your backyard, home garden, or a cornfield.”

The industry is still learning about the variables that can impact the efficacy of engineered nitrogen-fixing biologicals, he said. “Water content is a factor, soil makeup, temperature… You can have microbes that work really well in tropical settings and you take them to northern Germany and they don’t work anymore.

“The most important being the amount of nitrogen being fixed and transferred to the plant, but also selecting a chassis that has both stability and colonization properties, which are tougher to engineer.”

As an industry, he added, “We’re still learning how long do they stay attached to the plant and how long during the growing season are they still producing nitrogen and supplementing synthetic fertilizer?”

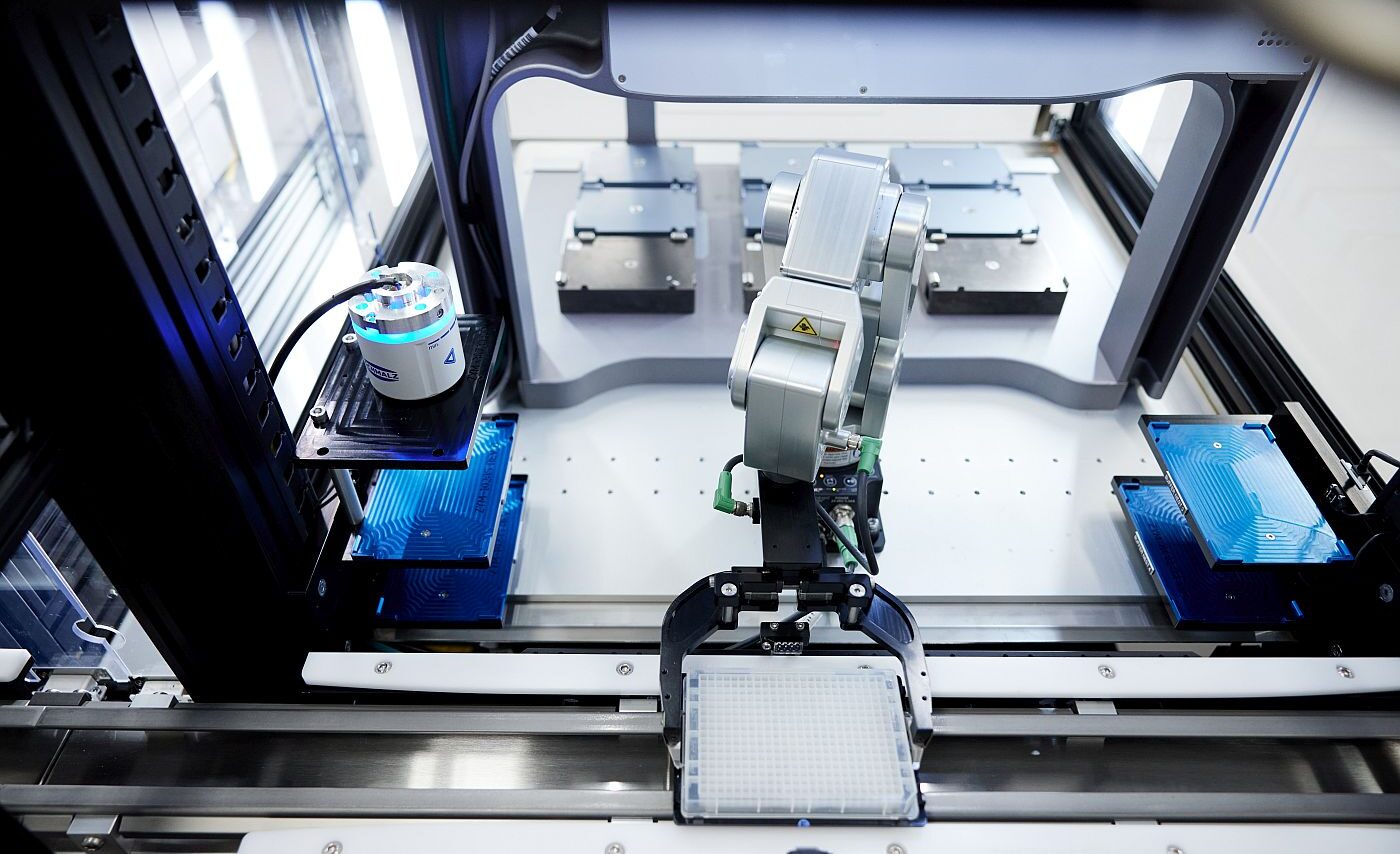

Image credit: Ginkgo Bioworks

Image credit: Ginkgo Bioworks

‘If can get that reduction in fertilizer input reduced by 25% or more, the economics become very compelling to the grower’

While California-based startup Switch Bio is pioneering an approach enabling engineered microbes to first compete and establish themselves on plant roots before switching on nitrogen fertilizer production, Ginkgo and Bayer are focusing on engineering a fix to the colonization challenge “rather than relying on some sort of a signaling mechanism,” said Miile.

However there is room for multiple approaches in this market, he stressed.

“Probably the solution is going to be a combination of things, because there are also other variables out there such as the availability of phosphate [if phosphate is limited, nitrogen-fixing microbes lack the energy needed to power nitrogenase activity]. At this point, it’s unlikely there’s going to be a single solution that’s going to magically enable a grower to cut the amount of synthetic fertilizer by half.”

So could microbial fertilizer options ever completely replace synthetic fertilizers?

“I think to get a reduction close to 40% would be an exciting outcome,” he said. “But if you can get that reduction in fertilizer input reduced by 25% or more, the economics become very compelling to the grower. That said, it’s a bit of a moving target as the price [of synthetic fertilizer] is always bouncing around.”

From an environmental perspective meanwhile, reducing the amount of nitrogen fertilizer sprayed on key crops by 25% would have a significant impact, both in terms of reducing the damaging effects of runoff and reducing greenhouse gas emissions produced from ammonia production, he said.

‘We’re hoping regulators catch up with the speed of innovation in this industry’

Owing to confidentiality agreements, Miile can’t share details on when Bayer expects to hit the market with a nitrogen-fixing microbial product but said: “We believe we’ll have products that significantly outperform the current products for foliar and in-furrow applications, but we’re also working on products that can be used as seed treatments with a much longer shelf-life.”

He added: “I can’t go into details about where the projects are, but I will say that [the] regulatory [approval process] is absolutely a factor [when it comes to the timing of a commercial launch].”

While nitrogen-fixing microbes are biofertilizers, a category generally quicker and easier to navigate than biopesticides from a regulatory perspective, oversight becomes more complex if you’re introducing genetically engineered microbes, he said.

“It’s very challenging in the US sometimes to run the type of field trials you want to, so you have to do them outside of the US. What we’re hoping in the ag world is that regulators catch up with the speed of innovation in this industry.”

The situation is somewhat easier for biologicals such as metabolites and peptides that are produced by genetically engineered microbes, he said, because the GMO is not itself entering the market.

Image credit: Ginkgo Bioworks

Image credit: Ginkgo Bioworks

Beyond nitrogen-fixing

Asked what else Ginkgo’s ag bio business is working on, Miile said: “We’re working a lot with partners from Brazil as biologics are growing faster there than anywhere else. We provide them with advanced leads in key areas around disease and pest control, but we also take their product and help make it better, so we take strains they have and optimize them.”

He added: “One area we see growing over the next three to four years is around metabolites or actives as biochemical pesticides that we identify and then produce from microbes in a fermentation tank and isolate. They really have the ability to compete with synthetics in terms of efficacy and cost.

“The other thing is proteins and peptides, which is an area where Ginkgo has a lot of experience on the biotech, pharma side.”

‘We’re trying to rethink how work gets done in the lab, and a big aspect of that is AI driven’

Another major area of focus at Ginkgo is around automation using modular automation units acquired from Zymergen [a biotech company acquired by Ginkgo in 2022] and “building those out to deal with high throughput and complex process needs in the laboratory,” he said.

“We’re basically trying to rethink how work gets done in the lab, and a big aspect of that is AI-driven. It’s all about the marriage of automation with AI to significantly improve the productivity in the research lab, whether it be in biopharma or ag.”

He added: “I think it’s going to be really exciting to see the type of products and the quality of product that start to come out in biologicals over the next five years. We’re going to be a step change in terms of performance and consistency.”

Further reading:

?? Switch Bioworks: ‘Just replacing 25% of nitrogen fertilizer with biologicals at yield parity would be game changing’

Pivot Bio talks insets vs. offsets, paying farmers, and why nitrous oxide is an overlooked emission

Why Ginkgo Bioworks partnered with Brazilian biologicals co Vitales: ‘It will speed up economically viable product concepts’

Exacta Bioscience teams up with Ginkgo Bioworks to address scalability challenge for biologicals

The post Inside Ginkgo and Bayer’s quest to rewrite the fertilizer rulebook: The race to create next-gen nitrogen-fixing biologicals appeared first on AgFunderNews.